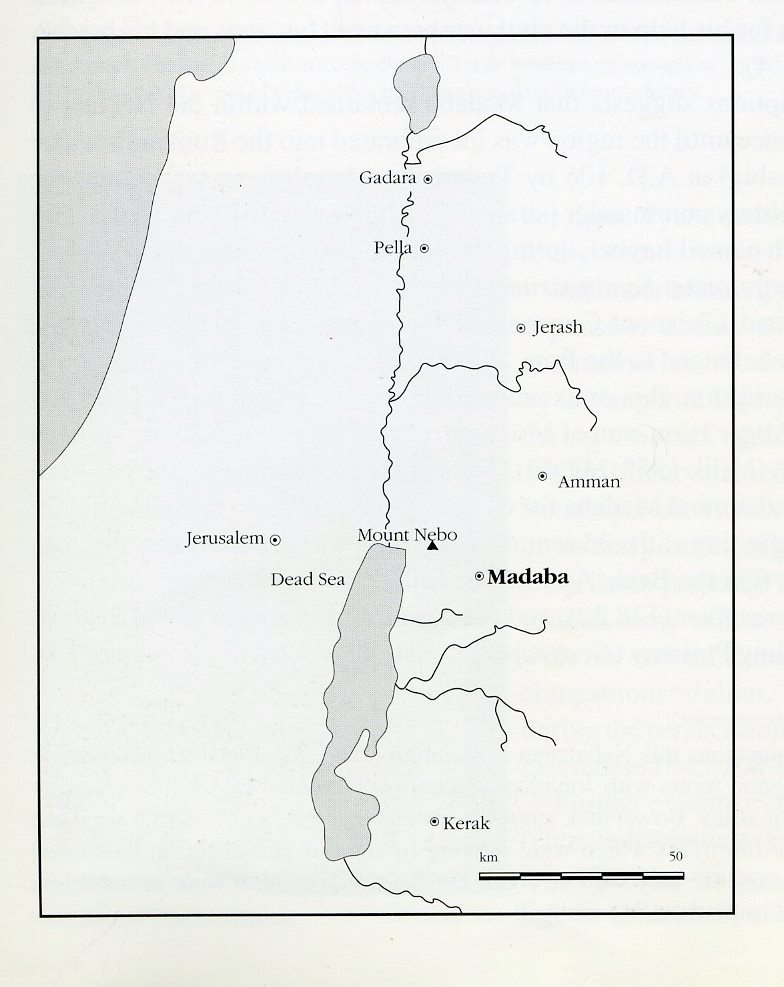

Modern Madaba, 30 km southwest of Amman, continues an urban tradition that can be traced back at least 4,500 years. The ancient settlement, now mostly buried beneath the modern town, lies on a natural rise created by branches of the Wadi Madaba. On and around the tell are the remains of the classical town, represented most notably by the churches and mosaic pavements that have brought Madaba so much fame. The earliest reference to Madaba occurs in the Bible (Numbers 21:30) as part of a lament describing the conquest of a series of Moabite cities including Madaba by the Amorite King Sihon of Heshbon.

Madaba continued to play a role in regional conflicts and, during the Hellenistic period, the “sons of Jambri,” apparently members of a Nabataean tribe from Madaba, were accused of ambushing a passing caravan in ca. 160 B.C. and killing John, the brother of Judas Maccabeus (I Maccabees 9:35-42). In retaliation, his brothers Jonathan and Simon attacked a Jambri marriage celebration, killing many in revenge. The region was incorporated into the Roman Province of Arabia in A.D. 106, following Trajan’s defeat of the Nabataeans at Petra. Christianity gained a foothold in the Madaba region during the late Roman period. There is evidence of a bishop in Madaba as early as the middle of the 5th century. The mosaic pavements of the region have proved to be a rich source for Madaba’s ecclesiastical history.

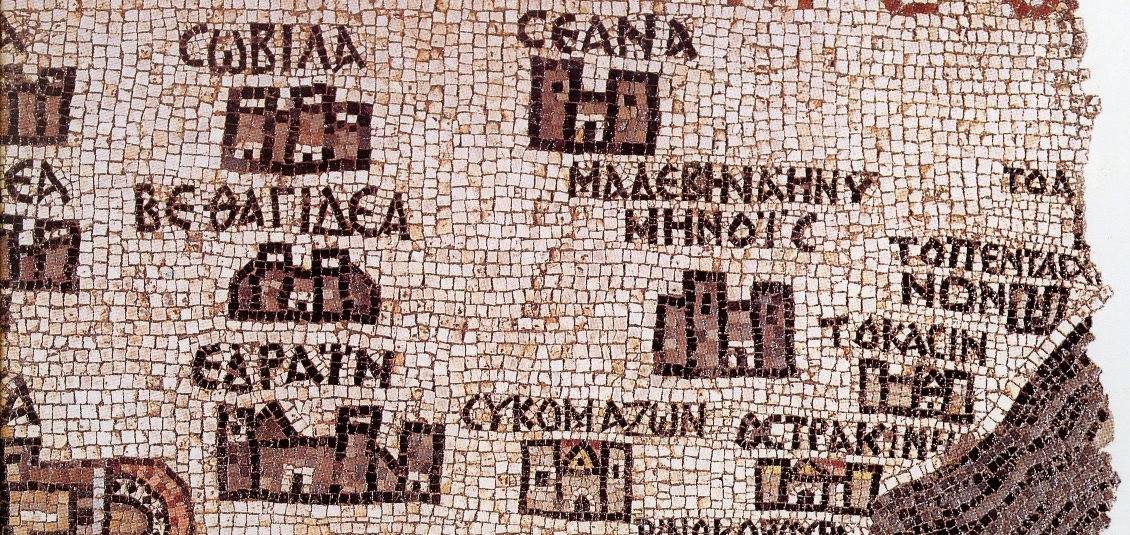

Madaba flourished during the reign of the Emperor Justinian (A.D. 527-65). An inscription found on the plastered wall of a large cistern to the north of the Church of St. George credits him with the renovation of the structure. During the 6th to 8th centuries, the church with the famous mosaic map of the Holy Land, the churches along the Roman street, the Burnt Palace and the Hippolytus Hall were built. Following the Islamic conquest and the establishment of the Umayyad caliphate in Damascus, the city of Madaba continued to flourish.

The excavations at the Burnt Palace demonstrate the richness of the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods. Far from being economically impoverished, those periods witnessed remarkable building activities. When one considers the fate of the antique cities of Syria which entered a phase of gradual decline from about the middle of the 6th century, Madaba appears as an exception to the general trend. The literary record falls silent about Madaba from the 8th until the early 19th century, when western Europeans began arriving in the Near East in search of adventure and traces of the past.

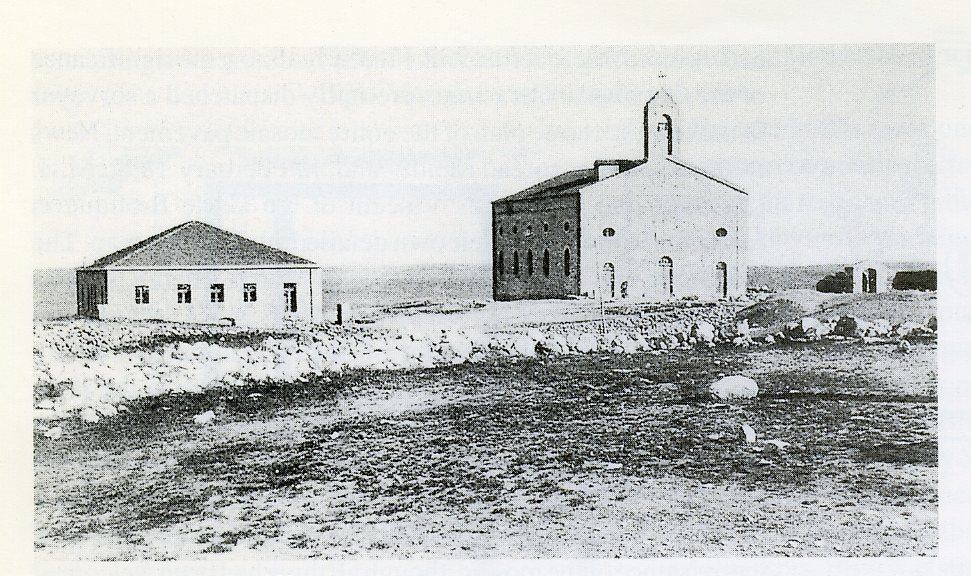

In 1806, the German explorer Ulrich Seetzen was the first European to visit Madaba. The famous Swiss “discoverer” of Petra, Johann Burckhardt, followed a few years later and recorded the considerable water collection and storage facilities near Madaba. Neither explorer noted any settled population in the region. With the discovery of the Moabite Stone at Dhiban in 1868, international interest in what was then called Transjordan increased dramatically and a flurry of expeditions soon began. Of these, the most successful was led by H. B. Tristram in 1872. The impressive extent of Madaba’s ancient ruins prompted Tristram to observe: “Excavations we were not able to attempt; but I have seen no place in the country where they seem more likely to yield good results.” Tristram also stated that much of the surrounding country was being cultivated by Beni Sakhr Bedouin. Claude Conder visited Madaba in 1881 and noted the presence of a group of Christians who had recently arrived from Kerak and were then living in caves. As those families moved on to the tell itself, often building directly on the foundations of ancient structures, they came upon mosaic after mosaic. Many were incorporated as floors in the new houses being built by the settlers. The announcement in 1897 of the discovery of a map of the Holy Land dating to the Byzantine era created a sensation. By the end of the first year alone, well over a dozen studies had appeared analyzing its contents. By the end of the century, the majority of the known mosaics of Madaba had been at least partially uncovered. In most cases, they were preserved and can be seen today.

Political unrest began to destabilize the region in 1905, making exploration more difficult; in 1916 the Arab Revolt began. Madaba would produce only a few archaeological discoveries in the next decades. The construction boom that followed the end of World War II, however, uncovered many new traces of Madaba’ s past. In 1962, the Department of Antiquities opened an archaeological museum in Madaba. Several adjoining houses where mosaic pavements had been discovered, southwest of the acropolis, formed the nucleus of the museum. The mosaic discoveries of the past century, while rightfully earning Madaba the title “city of mosaics,” have also brought concerns for their preservation. Individual mosaic pavements have received special attention from time to time, most notably the restoration of the map mosaic in 1965 by specialists from Germany. Until recently, however, there has been no systematic effort to preserve these priceless treasures of the town’s rich architectural heritage. The need for preservation became even more acute during the building boom of the 1970s and 1980s. As a result of the need for conservation of Madaba’s heritage, the Madaba Archaeological Park project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), evolved. In a related project, under a grant from the Canada Fund to ACOR, buildings within the park were renovated for use by the Madaba Mosaic School, a project of the Government of Italy to train mosaic conservators.

This blog is drawn from Timothy Harrison’s article “History of Madaba” in the 1996 ACOR publication Madaba Cultural Heritage edited by Patricia M. Bikai and Thomas A. Dailey.